August 2013. The black population in South Africa has increased by an astonishing 920 percent in just 100 years, mainly thanks to white farmers and western infrastructure, a new report from the Transvaal Agricultural Union (TAU) has revealed.

The report, titled “Whose Land is it Anyway,” was brought out to counter the build-up to the centenary of the 1913 Land Act in South Africa, which black supremacists and their supporters quite falsely claim was a “cornerstone of apartheid” and “land theft” from the African people.

The TAU is the oldest agricultural union in South Africa and has been in existence since 1897.

“Common currency has it that whites ‘stole’ land from indigenous blacks and that this theft was legally ratified by the 1913 and 1936 Land Acts which divided up the land and codified these divisions,” the TAU report said.

In reality, “whites who came to South Africa in 1652 and thereafter found a land devoid of basic development and infrastructure, sparsely populated by meandering tribes who had no written word and whose way of life was the absolute antithesis of Western mores.

“It is now acknowledged that the Khoi-San groups, and their sub-groups, are the indigenous peoples of South Africa.

“Whites and black African groups arrived in various parts of the country around the same time. They met at the Fish River in the Eastern Cape, and wars followed.”

The TAU also pointed out that prior to the arrival of the whites, the black population—which as pointed out above, arrived simultaneously with the European settlers and therefore have no more claim to the country than the whites—did not have any concept of land ownership or even writing.

“Man in his primitive state did not know the concept of ‘land tenure,’” the report continued.

“When hunter/gatherer groups formed, the first land tenure (if it can be called that) was by nature communal. Before the arrival of the European in South Africa with his tradition of individual land ownership, communal tenure in Africa was the norm.

“The territory inhabited and/or cultivated by a particular ethnic group was owned and/or utilized by the tribe in the name of their king or chief. Because there was no written word among these peoples, Christian missionaries took it upon themselves to learn and then write and codify the languages of the black people to whom they were ministering. They then taught these people to read and write their own language.”

“It is known that a great migration of black people took place from the Great Lakes region southwards, eventually reaching Southern Africa. Numerous reports exist as to which tribe went where. But these reports are not the historical property of the black peoples.

“Thus their claims to land in South Africa have no empirical foundation. They are based on oral history and folklore, and what was observed by early European travelers and missionaries, by the British colonial presence in the country, by Boer trekkers and administrators.

“If your history is written by others, with what can you contest this history? However, the early settled areas of the black people were later generally recognized as their core areas.”

“From the very beginning of settlement, black and white were segregated. South African history is replete with clashes over land ‘ownership’. There were no title deeds, no courts to decide who owned what.

“Proclamations and annexations were followed by wars, clashes, agreements and disagreements, theft of livestock, sloppy boundaries and arguments over the measurement and surveying of land; borders were drawn and re-drawn; people moved all over the place and a completely differing approach to farming by both groups existed.

“In the black community, land was communal and the product of their agricultural activities was mainly for their own consumption. This was subsistence farming, and it persists in today’s South Africa.

“ Soon after the formation of the Union of South Africa in 1910, it was deemed imperative to settle the land question once and for all. The government (still under the British Crown) believed that if land could not be partitioned and allocated within the ambit of a Western title deed system, the very future of South Africa would be put at risk.

“The most immediate problem was food production for a burgeoning population. (It was obvious to the British then that blacks could not produce food for surplus, and to this day this is still the case).

“The core reason for the 1913 Land Act’s passing was the security of the whites, and particularly the farmers, to give them the necessary security of tenure on their farms to produce the food for what was still a country under the British flag, controlled essentially from London. Gold and diamonds had been discovered, and Britain was not going to give up this new jewel in the Crown.

“Antagonists of the 1913 Act and indeed the 1936 Act should look to Britain for redress. These pieces of legislation were not apartheid Acts—they were devised in South Africa under a government controlled by Britain.

“The current population of South Africa according to Stats SA is 52,98 million. As quoted by the SA Institute of Race Relations’ Yearbook 2012, the population of the country in 1911 was blacks: 4,018 million, whites: 1,276 million; coloreds: 525,466 and Indians: 152,094.

“The percentages were white: 21% and black: 67%. One hundred years later, the percentage population increase of blacks was 920%.

“But land in South Africa is a political tool. It is wielded without thought for the morrow. It is proffered within the context of a cultural more that has no place in today’s practical world. The division of land under the 1913 Land Act is a blunt weapon used to garner votes by the present SA government to seduce naïve and mostly uneducated followers who cannot feed themselves but who are asked to look upon those who can feed them as ogres who stole their land.”

Recent statistics published by the SA Institute of Race Relations state there were 1, 337,400 units of food production in South Africa. Of these, 1,256,000 are subsistence farmers; 35,000 communal area farmers have turnovers of less than R300,000 per year; 24,000 small commercial units have turnovers of less than R300,000 per year, and only 22,400 commercial units have turnovers of more than R300,000 per year.

“This means that only 6 percent of farmers in South Africa produce 95 percent of the food for 53 million people.”

Finally, the report points out that leftist “harping” on the “inequities of the 1913 Land Act are completely at variance with the facts as they existed in the first ten years of the twentieth century.

“Government (and many organizations with strange agendas) continues to harp on the perceived unfairness and injustice of the divisions of land set out in the 1913 Land Act without taking into account South Africa’s pre-1913 recorded history and, importantly, the population of the country at the time.”

There’s a bit of a discrepancy here: you say that the whites and blacks in SA ‘met at the Fish River’, and that’s superficially true.

1) It’s more or less the limit of the summer-rainfall region, outside of which the Bantu couldn’t grow their staple food crop, sorghum. Cassava, yams and millet, found elsewhere in Africa, can’t grow in S Africa’s cold, super-dry winters.

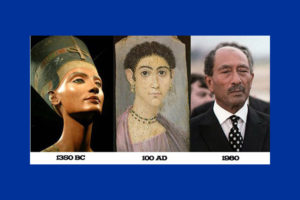

2) Genetic mapping elsewhere in this website, as well as archaeology, shows that the predecessors of modern black ethnic groups were already present around AD200

3) The land could, however, have been emptied by Mzilikazi and the Difaqane, when renegade Zulus went on a rampage in the high-lying interior of the country. It had just ended when the Voortrekkers migrated north. The BaSotho and BaTswana came out of hiding and more or less said, ‘Where did all these whites come from?’

Otherwise, spot on.