Chapter 55: The White Man’s Burden—South Africa

The story of the white settlement of the southernmost part of Africa differed from all the other European colonization experiments in one important way: only in South Africa did whites remain a minority yet settle in sufficient numbers to temporarily create a First World environment.

This was however exacted at a huge cost, both from the natives and ultimately, from the white settlers. The history of South Africa serves, therefore, as a valuable lesson in racial dynamics and the interrelatedness of demographics, race, and cultural makeup. It is the most perfect modern example of the unbreakable principle of nature: that a race which makes up the majority population in a territory, ultimately determines the nature of the civilization in that region.

First White Settlement 1652

The first major permanent white settlement in southern Africa was started in 1652, when the Dutch East India Company sent one of its officials, Jan van Riebeeck, to the tip of the continent in what is present-day Cape Town. Van Riebeeck was ordered to build a supply station for ships traveling to and from Asia. A number of the structures he ordered built, including a fort and the first large storage barn, are still in existence in Cape Town.

Van Riebeeck’s expedition encountered small groups of Bushmen and Hottentots at the Cape. These were racially distinct from the African tribes, who at that stage were still concentrated on the east coast and more than one thousand miles from the Cape.

Dutch settlement leader Jan van Riebeeck (1619–1677) lands at the southernmost point of Africa in April 1652. Shown here are some local Hottentots, the only nonwhites present at the time. The blacks were still nearly one thousand miles from the Cape of Good Hope, where Van Riebeeck was tasked with building a halfway supply station for ships on their way to the Far East. During the time he was governor (1652–1662), Van Riebeeck built a fort, dredged a part of the bay for use as a harbour, and supplied fruit, vegetables, and meat to passing ships. A series of clashes with the local nonwhites forced Van Riebeeck to plant a huge almond hedge as a barrier between the Europeans and the Hottentots.

“Free Burgers”—the First White Farmers

By 1657 it became evident that the Dutch East India Company’s farming efforts were inadequate to supply both passing ships and the growing white settlement. A small number of Company employees were released from their contracts and allocated land which they worked as independent farmers. These first white farmers in South Africa were called burgers, the Dutch word for “citizens,” to which the word “free” was added as a sign that they were no longer employees of the Company.

Between 1680 and 1700, the Dutch encouraged white immigration in ever-increasing numbers to bolster the settlement. Their own nationals were joined by groups of Germans and French, the latter being Protestant Huguenots who escaped Catholic persecution.

The demand for labor caused by the expanding farming settlements was met by the importation of slaves from the Dutch colony in Malaysia and by small numbers of black slaves brought in from the then still-unexplored interior.

Bushmen Immigrate North

Relations between the settlers and the Bushmen were rocky. Large numbers of the natives died from European-borne diseases to which they had no resistance, and the rapidly-growing numbers of white settlers quickly took up much of the land around the Cape.

As the Hottentots and Bushmen were nomads with no concept of land title, there was no specific “homeland”which the Europeans took away, but as their farms spread, the space in which the natives could roam was steadily decreased.

The settlers also suffered greatly from stock theft and other petty crimes committed by the natives. A series of very one-sided clashes took place and the Bushmen migrated north to get away from the European settlement. They settled in what later became South West Africa, today called Namibia, where their descendants still live.

The castle at Cape Town, on the southern tip of Africa, is the oldest building in South Africa. First erected by Jan van Riebeeck in 1652, it was rebuilt in stone in 1666, and has remained largely unchanged from that time. The sketch below shows the original Dutch design, and the photograph shows the fort in 2010, over three hundred years later. The castle never saw military action, despite being built specifically for that purpose.

Mixed Marriages Prohibited 1685

The Dutch East India Company issued written instructions to its governor at the Cape, Simon van der Stel, to prevent all racial mixing and intermarriage. This order was given formal status in 1685, the same year that the first whites-only school was established for the colonists’ children.

The Dutch had good cause to be concerned over the frequency of racial mixing. Despite the prohibition, mixing between the Malays, the remainder of the Hottentots, blacks, and a number of whites produced a mixed-race group which became known as the “Cape Coloreds.”This group grew in number until they surpassed the white population, and some were so “white-looking” that they were ultimately classified as such by the later white governments.

Boers Emerge as a Distinct Identity

The growth in the number of African-born white settlers created the genesis of a new cultural identity, as was the case in the Americas and elsewhere. Dutch, German, French, and even Scandinavian elements joined together and became known as “Boers,” the Dutch word for “farmer.” The Boers who moved into the interior became isolated from changes at the Cape, and continued to speak a form of old Dutch, which later was transformed into the language of Afrikaans.

First Encounter with Blacks: Nine “Kaffir Wars” Erupt

The Boers pushed eastward along the coast in their ever-growing quest for new farmland, and eventually encountered the first major black tribe, the Xhosa, in the region now known as the Eastern Cape, some eight hundred miles from Cape Town. The distance involved and the time it took for this first meeting to occur—nearly 120 years—serves to underline the fact that large parts of southern Africa were uninhabited at the time of the first European settlement at the Cape.

The Xhosa tribe was migrating south at the time, and after the two races met in the Eastern Cape, both migrations came to an end along the Fish River. Both sides were dissatisfied with the other’s presence, and nine border wars between the races, known as the “Kaffir Wars,” broke out between 1781 and 1857. (Although the term “kaffir” has taken on a racially derogatory meaning, at the time of the colonial era, it had no racial meaning at all. The word is of Arabic Muslim origin, khufr, and in fact means non-Muslim, or infidel, and was thus applied to any race. The Europeans adopted it to refer to the black’s paganism, and only later was a racial meaning given to the word.)

The Kaffir Wars ended after the Xhosas foolishly believed one of their witchdoctors who told them that if they killed all their cattle, their ancestors would rise from the dead and drive the whites into the sea. In February 1857, the Xhosas killed their cattle but waited in vain for the promised ancestor uprising. After several weeks, Xhosa power had been destroyed by a combination of starvation and disillusionment.

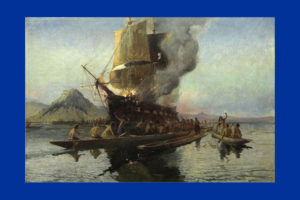

A scene from the 1835 “Kaffir War,” one of a series of conflicts which erupted after the white migration which traveled northeast from Cape Town came to a halt when it encountered the southward migration of the black Xhosa tribe. The ongoing wars persuaded many white settlers to leave for the interior where they hoped life would be more peaceful.

The British Occupy the Cape Colony

The advent of the Napoleonic Wars in Europe saw the British seize the Cape from the Dutch out of fear that they would turn it over to the French. As a result, British troops landed for the first time in 1795, although they left during a short period of peace in Europe. A new outbreak of war with France saw the British return to the Cape in 1806, after which their occupation became permanent.

At the end of the Napoleonic Wars, Britain formally purchased the Cape from the Dutch for six million pounds. At this stage (1806), the Cape Colony had a white population of twenty-six thousand, a slave population of some thirty thousand, and an estimated Cape Colored population of twenty thousand.

Mass British Settlement 1820

In 1820 the British settled over three thousand volunteer colonists, with government aid, in the Eastern Cape to strengthen the white population in the face of the then ongoing Kaffir Wars. This influx boosted the white population along the border area by 12 percent, and also caused an Anglicization which antagonized the Dutch-speaking Boer population. The Anglicization policy soon became official. In 1822, English became the sole official language. All laws and official business was conducted in English, which put the Boers at a disadvantage in commercial and social environments.

The British administration also passed labor laws in 1822 which for the first time included the Cape Colored population, and went on to abolish slavery in 1833. The British government offered a compensation payout to the former slave owners, but the money had to be collected in London, making any payment impossible. All these measures served to sow discord between the British government and the Boers and set the background for the next 150 years of white history in South Africa.

The dangers of settling in southern Africa in the early 1800s were so well known that they became the subject of satire, as illustrated in this cartoon which appeared in a London journal in 1820. This was the same year that thousands of British settlers went to the Eastern Cape. Although cartoonish in character, virtually all of the incidents depicted here actually happened—and many worse incidents took place as well.

The “Great Trek” Starts 1836

Faced with increasing Anglicization and the seemingly endless wars with the Xhosa, some Boers along the eastern border took the momentous decision to leave for the interior where they believed they would be free of both these impediments and also independent of all foreign governments.

In 1836, the first of some fifteen thousand Boer families packed their goods into canvas-covered wagons and set off for the interior. This movement, known as the Great Trek, was the catalyst which definitively created the identity of the people who won world fame as “Afrikaners,” although then they were more commonly called Trek Boers.

The trepidations suffered by the Boers on the Great Trek easily rivals that of the great Western Trails across America. The Trekkers had to cross the highest mountain range in southern Africa, called the Drakensberg (or the Dragon Mountains, a well-deserved name) in their wagons and, to their disappointment, were faced with black tribes equally, if not more, hostile than the Xhosas.

The dangers of the Great Trek were highlighted by the fact that the first two exploratory expeditions ended in failure. The first was wiped out in a clash with blacks in the present-day far north of South Africa, while the second barely survived similar attacks only to be decimated by malaria.

The First Boer Republics: Winburg and Potchefstroom

At first, the trekkers migrated north and crossed over the Orange River into what later became known as the Orange Free State. There they found the land mostly uninhabited as it had been cleared of its sparse population by an inter-black war known as the Difaqane. This conflict had been caused by a series of raids organized by a Zulu tribe who later took on the name of their greatest chief, Mzlikazi, or Moselekatse, and are today known as the Matebele.

Matebele raiding parties detected the presence of the Trek Boers and attacked a Trekker settlement without warning in 1836 at a place called Vegkop (“fighting hill”).

The Matebele were decisively defeated and fled north across the Limpopo River. There they settled in the country now known as Zimbabwe, where they are one of the two major tribes.

The Battle of Vegkop in 1836, at which a hundred Voortrekkers were attacked by thousands of Matabele tribesmen, ended in a decisive defeat for the natives. The Matabele were driven over the Limpopo River into what is today the country of Zimbabwe, where they remained ever since. This picture is interesting from another perspective: on the far left, a black servant is visible. From the very beginning, the Boers kept large numbers of black servants to do all the manual labor, and it was this reliance on nonwhite labor which ultimately led to the downfall of white South Africa.

The Trekkers founded the town of Winburg (literally, “Winning Town”) in 1837 to commemorate their victory and declared themselves independent, using the town’s name as the title of their country. The Trekkers elected a representative parliament and a “Commandant General” by the name of Piet Retief.

To the north of the Republic of Winburg, another group of Trekkers established in 1838 a second state which they called the Republic of Potchefstroom, named after a town which they had founded. The Republic of Potchefstroom elected the Trekker leader Andries Potgieter as its head of state.

These two republics merged to become the Winburg–Potchefstroom Republic, but Trekker unity was short-lived. Arguments over the future direction of the Trek flared up, and Retief decided to lead his followers east over the Drakensberg Mountains to establish a new state of their own. The only problem with his plan was that on the other side of the mountains was the heartland of the Zulu tribe.

Retief Murdered by the Zulus

Retief decided to try and negotiate with the Zulu king, Dingaan, for a piece of territory which had few Zulus living in it. He left the majority of his trek party encamped by the Blaukraans River and took a seventy-strong delegation to meet with the Zulu king at his major settlement, Umgungundlovu.

The negotiations appeared to be successful, and in return for the recapture of some cattle stolen by another chief, Dingaan agreed to give the Boers land. Retief appeared to have been successful, but he and his party were ambushed by Zulus at a celebration hosted by Dingaan and cruelly killed on February 6, 1837.

February 6, 1838: With the cry of “Kill the White Wizards,” the Zulu king Dingaan orders his tribesmen to murder the unarmed Voortrekker party under Piet Retief. The Trekkers came to the Zulu chief to try and negotiate land upon which to settle. Some artistic liberty has been taken with this nineteenth century illustration, as Retief and his party were impaled and clubbed to death outside the main settlement. The treaty which he and Dingaan had signed, granting the Trekkers territory, was found later with Retief’s body.

News of the betrayal and murders did not reach the remainder of Retief’s Trek party, and they were attacked by a ten thousand-strong Zulu force ten days later. Some 300 whites were killed in the attack, including 41 men, 56 women, and 185 children. This figure, when added to the seventy men killed with Retief, meant that more than half of the Retief Trek party had been killed in less than two weeks. The scene of the massacre was named Weenen, or “weeping” in Dutch. A town was later established nearby and was also named Weenen to commemorate the massacre.

The British had in the interim established a post along the coast, which became known as Port Natal. This settlement, which is the present-day city of Durban, was attacked by the Zulus after the massacre at Weenen in an attempt to drive all whites out of the region. The British garrison, although heavily outnumbered, fought back with fierce determination and the Zulus were driven off.

The Battle of Blood River 1838

The Boers set off in pursuit of the Zulus with a force which they called a “punishment commando” under the command of Piet Uys and Andries Potgieter, who had come to the aid of the Trekkers from the Winburg–Potchefstroom Republic. This attempt to defeat the Zulus ended in failure when Uys was defeated and killed at the Battle of Italeni on April 9, 1838. Potgieter’s force, which had split from Uys as the result of a personal argument between the two men, was outnumbered and fled the field. It was derisively called the Vlugkommando (or the “fleeing commando”) and Potgieter left Natal immediately afterward to go back to his own republic on the other side of the Drakensberg.

News of the defeats and massacre resulted in a new wave of support and volunteers from the Boer population in the Cape. Chief among them was a dynamic leader named Andries Pretorius, who upon his arrival was selected to be the Boer’s Commandant General by a popular vote amongst the trekkers.

Within a week, Pretorius had organized a commando which consisted of 451 men, including three Scotsmen from Port Natal, and set off in pursuit of the Zulu army. After six days of running battles with Zulu patrols, Pretorius set up his camp at the confluence of an erosion ditch and the Ncome River. The commando’s sixty-four wagons were drawn into a closed formation called a “laager” in Dutch, and the gaps were strengthened with wooden shutters and thorn bushes. Pretorius also possessed three cannon which he deployed at strategic points along the wagon perimeter.

The Calvinistic Boers then took a vow to God that if they were granted victory, they would hold the day sacred forevermore. This was the origin of the celebration called the “Day of the Vow”which was celebrated right until the end of white rule in South Africa in 1990.

The Zulu army attacked Pretorius’s camp on December 16, 1838, with a force estimated to be between ten thousand and thirty thousand strong. The battle was uneven as the whites’firearms and cannon mowed down the Zulus. Thousands of blacks were killed and the Ncome River literally ran red with their blood, so that it was renamed Blood River. The unevenness of the clash was illustrated by the fact that only two whites suffered light injuries during the entire battle.

The epic Battle of Blood River, fought on December 16, 1838, saw 451 whites defeat a Zulu army numbered in the tens of thousands. The Zulus wanted to attack at night, but were frightened away by what they thought were ghosts over the wagons, but which were actually lanterns hanging at the end of long oxen whips. The Zulus were confronted with rifles, cannon, and a cavalry charge, the latter of which, unleashed by the Voortrekker commander Andries Pretorius at a critical moment in the battle, broke the Zulu ranks. After this victory, the white settlers formed the first independent Boer state in the region, Natalia. However, the area was annexed by Britain a short while later, and many of the Trekkers emigrated to the newly-established Boer republics in the interior. Pretoria, the capital of the most famous Boer republic, was named after Pretorius.

The Republic of Natalia

The defeat of the Zulu army allowed the Boers to establish their first independent republic called Natalia in 1839. They established their capital at a settlement which is the present-day city of Pietermaritzburg, named in honor of Piet Retief and another Trekker leader, Gerhard Maritz. In this town the Boers built a church to commemorate the vow taken at the Battle of Blood River.

The Republic of Natalia was acknowledged as independent by the British in 1840—but it was anarchic, ill-planned, and short-lived. A series of clashes between the Boers, the Zulus, and even the Xhosa to the south, persuaded many in the Cape Colony’s government that Boer independence be brought to an end in order to preserve stability on the east coast.

Tensions between the Boers and the British, who kept their base at Port Natal, heightened to the point where war broke out in 1842. A British attempt to seize the settlement of Congella in May failed, but this was the only Boer victory of the conflict. The British rushed reinforcements to the region, and by 1845, Natalia had been annexed and incorporated into the Cape Colony.

Many Boers, including Andries Pretorius, then trekked back over the Drakensberg to join their compatriots in the independent states which had been established in the interior.

The Orange Free State and the South African Republic

While the drama in Natalia had played itself out, other Trek Boers had continued with the establishment of the fledgling Boer states in the interior. The Winburg–Potchefstroom Republic steadily expanded its claimed area of control and came into conflict with a black tribe called the Basotho who had migrated northward after the Boers.

A series of clashes took place and the British authorities at the Cape decided that, just like Natalia, stability demanded the crushing of Boer independence before all the native tribes were provoked into unrest. The British incorporated the area occupied by the Basotho tribe into a protectorate in 1868. This region was given independence in the twentieth century and is today the state of Lesotho.

The area south of the Vaal River was proclaimed British territory in October 1842, effectively ending the Winburg–Potchefstroom Republic. Some Boers accepted the extension of British control but others did not. The dissenters, led by Andries Pretorius, attacked a British army unit under the command of Sir Harry Smith at the Battle of Boomplaats in August 1848, but were defeated. Pretorius and his followers then migrated northward over the Vaal River and joined the other Trekkers already settled there.

The Winburg–Potchefstroom Republic area proved difficult to rule, with the black and white inhabitants alike engaging in a series of bewildering alliances, mostly against the British. Finally, the British government in London intervened and ordered the Cape authorities to formally recognize Boer independence north of the Orange and Vaal Rivers. This was given official status by the Sand River Convention of January 1852, and confirmed again in 1854.

The Boers living between the Orange and Vaal Rivers declared themselves independent in April 1854 as the Oranje Vrij Staat (the “Orange Free State”). The town of Bloemfontein, where delegates had met to draw up the new country’s constitution, was declared the capital. Significantly, the new state’s constitution granted the right to vote in elections to all “Europeans who [had] been present in the Republic for six months.”

The Boers north of the Vaal River followed suit. By December 1856, an elected assembly met at Potchefstroom, drew up a constitution, and adopted the name Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek (the ZAR, or in English, the “South African Republic”). The ZAR became better known by its colloquial title of the“Transvaal,” although that name was only formally given to the territory when it became a province of the Union of South Africa in 1910.

Initially the ZAR chose Potchefstroom as its capital, but in 1855 the newly-founded town of Pretoria, named after Andries Pretorius, became the seat of the Boer parliament and thus the country’s capital city. As was the case in the Orange Free State, voting rights were only granted to Europeans.

Left: Josias Philip Hoffman, first president of the Orange Free State, who served from April 18, 1854 to February 10, 1855. Right: Francis William Reitz, fifth president of the Orange Free State, who served from March 4, 1896 to May 31, 1902.

Indians Arrive in South Africa

By the mid-nineteenth century, South Africa had been divided between the British and the Boers. The British held the coast, while the Boers occupied the interior. The eastern coastal areas of Natal proved ideal for the cultivation of sugarcane, and after failing to get the black population to work as laborers, the British resorted to importing indentured Indian labor.

This influx created the basis for the Indian population of South Africa which is still centered in the KwaZulu Natal province. The government of the Orange Free State viewed the influx of Indians with alarm and brought in a series of laws which prevented Indians from gaining permanent residence inside its borders. These laws remained in force in the Orange Free State until the late 1980s.

The First Anglo–Boer War 1881–1882

The economies of the Boer republics were agriculturally-based, and, compared to the British-ruled Cape, relatively poor. The discovery of diamonds in the region known as Griqualand West—a region claimed by both British and Boers—caused a fresh wave of immigration from Europe. This consisted mainly of British immigrants, but also included a significant number of Jews who were to wield great influence in the economy of the country. The influx of British settlers strained relations between the Boer republics and the British administration even further.

By this time, the ZAR was economically on its knees, and threatened from at least two sides by hostile black tribes. In the northeast, an ongoing fight with the Pedi tribe resulted in a Boer defeat, while the revitalized Zulus threatened the eastern border.

The ZAR was also politically weak, and the growing anarchy in the republic caused many Boers to consider leaving or even asking the British to annex the territory. In January 1877, a tiny force of twenty-five British soldiers under the leadership of Sir Theophilus Shepstone, the former Secretary for Native Affairs in Natal, entered the ZAR. Shepstone marched to Pretoria and, after three months of discussions with the failing Boer government, hoisted the British flag in April 1877 and announced the annexation of the republic. The disillusioned Boers offered no resistance and Shepstone became the administrator of what was now called the “Transvaal Colony.”

It took three years and a herculean effort on the part of three young Boer leaders: Paul Kruger, Piet Joubert, and Marthinus Pretorius, to rouse their people into resisting the British annexation. Eventually, after a series of mass gatherings across the ZAR, the Boers rose in armed rebellion. On December 13, 1880, the three leaders proclaimed the restoration of the ZAR in the town of Heidelberg. The Boers raised an army of about 7,000 men against the total British occupation force of around 1,800 soldiers who were stationed all over the country.

The First Anglo–Boer War followed, and was marked by a series of four humiliating defeats for the British at the battles of Bronkhorstspruit, Laingsnek, Schuinshoogte, and Majuba. After this battle, fought in February 1881, the British government announced that it was prepared to restore self-government to the Boers. Three years of self-rule followed, and full independence was granted in 1884 by the London Convention after Paul Kruger was elected president of the ZAR in 1883.

The Battle of Majuba, February 1881. The British are defeated by the Boers and grant independence to them once again.

British Race War with the Zulus

By 1872, the white population of Natal had reached 17,500, compared to the estimated 300,000 Zulus. The Indian laborer population was around 5,800. From the Zulu point of view, the British were no better than the Boers, as both were invaders. The Indian presence was also resented by the Zulus, and a racial tension existed between these groups which periodically erupted into violent clashes.

The Zulu king, Cetshwayo, decided to expel the British from Natal in 1878, and for this purpose assembled a sixty thousand-strong army. The British authorities became aware of his intentions and invaded the area called Zululand in January 1879, with the intention of forcing Cetshwayo’s army to disband.

The Zulus struck first. On January 22, they attacked the main British force at an outpost called Isandhlwana and in a fierce one-day battle, killed all but six of the 1,500 white soldiers. The Zulus pushed home their attack and sent a force of about 4,000 warriors to attack a tiny British outpost of 140 men at Rorke’s Drift, a short distance from Isandhlwana. Hours of bitter hand-to-hand fighting followed, and in the morning the Zulus gave up and retreated after suffering heavy losses.

The British brought in reinforcements and defeated the Zulus at the Battle of Khambula fought at the end of March. In July, the Zulus suffered a final defeat at the Battle of Ulundi, which ended Cetshwayo’s plans to expel the whites from Natal.

Rorke’s Drift, a British supply base in Zululand, located at a mission station, became one of the British Army’s most renowned battlefields during the night of January 22, 1879. Only 150 British soldiers defended it against thousands of Zulus, who, despite their overwhelming numerical advantage, were unable to break the white soldiers’ solid defense. Fighting went on all night, and by dawn, the Zulus were forced to retreat, leaving at least 351 of their number dead outside the British stockades. Eleven Victoria Crosses were awarded to the men who fought at the battle, the largest number given to any single battle before or since.

Second Boer Republic in Natal

The Anglo–Zulu War had an unexpected consequence for the British. The confusion in Zulu ranks following the downfall of Cetshwayo saw two contenders, Usibhepu and his nephew Dinizulu, each claim chiefdom of the tribe.

Dinizulu called upon local Boers to support his claim and a group under the command of Lucas Meyer helped suppress Usibhepu’s followers. The grateful Dinizulu gave the Boers a large piece of land in return for their services, and on August 16, 1884, Meyer proclaimed another Boer state, the Nieuwe Republiek(“New Republic”) with the town of Vryheid (“freedom”) as its capital. Four years later, the New Republic amalgamated with the ZAR.

The Second Anglo–Boer War 1899–1902

The 1886 discovery of gold in the south of the ZAR caused a new flood of British and Jewish fortune seekers to enter the Boer republic. In the town of Johannesburg, founded at the center of the gold bearing reef, British and other non-Boer elements soon greatly outnumbered the Boer population.

Fearful of losing political control, the Boer government refused to grant these new immigrants voting rights, classifying them instead as Uitlanders(“foreigners”).

The Uitlander question proved to be the spark for the Second Anglo–Boer War of 1889–1902. Protracted negotiations between the British administration at the Cape, headed by Cecil John Rhodes, and the Boer president Paul Kruger, over the rights of the Uitlanders broke down and an armed rebellion broke out in Johannesburg in 1895. Simultaneously a small private militia under the leadership of one of Rhode’s adjutants, Leander Starr Jameson invaded the ZAR to support the rebels.

The invasion and rebellion were suppressed by Boer forces, but the die had been cast. War between the Boer republics and the British was inevitable.

Boer soldiers in the field during the Second Anglo-Boer War.

Boers Strike First

Tensions heightened over the next three years, and in 1899, the British moved large numbers of troops up to the borders of the Boer republics in preparation for an invasion. ZAR President Kruger sent an ultimatum to the British administration in the Cape saying that it would be regarded as an act of war if the troop buildup was not halted. The ultimatum was ignored, and in October 1899, the two Boer republics jointly launched preemptive strikes against British forces in Natal and the Cape Colony.

At this stage the total white population of both Boer republics was just over 200,000. Of this number they produced an army which at its strongest totaled around fifty thousand men. To this figure was added another two thousand Boer sympathizers recruited from the Natal and the Cape Colony.

The British had 176,000 soldiers in the Cape Colony alone at the end of 1899. By the end of the war, the British had deployed around 478,725 soldiers in the campaign, more than twice as many as the entire Boer population, men, women, and children included.

Initial British Defeats

At first the war went well for the Boers. Several British defeats followed in quick succession and the Boers laid siege to the towns of Mafikeng and Kimberley in the Northern Cape, and Ladysmith in Natal. It was these sieges, however, which cost the Boers the initiative and ultimately the war.

Initially, the Boer plan had been to strike deep into Natal and seize the port of Durban, while simultaneously seizing the large ports in the Cape: Port Elizabeth and eventually Cape Town. However, the Boer forces became bogged down in the strategically unimportant sieges which were far from their original targets, and the British were able to land large numbers of reinforcements.

Nonetheless, the British suffered a number of defeats in the initial phases of the war, particularly in the period December 10–15, which was known as the “Black Week.” The battles of Stormberg, Magersfontein, and Colenso took place during this time and all were marked by huge losses for the British and victories for the Boers.

The British invade the Orange Free State with a main column of forty-two thousand men and 117 guns in May 1900. This was part of a force which eventually saw more British soldiers deployed than the entire Boer population: men, women, and children, combined. Against such odds, the Boers stood no chance.

Inevitable British Victories Due to Overwhelming Numbers

The British had in the interim reinforced their South African army and pressed home their overwhelming military advantage. The Boer sieges were lifted and a series of engagements pushed the Boers back into their home territory. By March 1900, the capital of the Orange Free State, Bloemfontein, had fallen to the British commander, Field Marshall Lord Roberts. The Orange Free State was formally annexed on May 28 and renamed the Orange River Colony.

By September 1900, the main British column took Pretoria, which was surrendered without a fight. The ZAR was formally annexed on September 3, and renamed the Transvaal Colony. The fall of Pretoria convinced Roberts that the war was now over. He was wrong.

The remaining Boer forces, now numbering only some twenty-six thousand, launched a hit-and-run guerrilla war which lasted another two years. Their soldiers operated in commandos in the open veld and could rely on supplies provided by the rural Boer community.

The British first attempted to break the Boer guerrilla war by erecting a series of blockhouses across the country connected with barbed wire. This only proved to be a minor hindrance to the mobile Boer units, and provided a new target for sabotage attacks.

Scorched Earth and Concentration Camps

The ongoing war started to take a financial toll on the British government. Eventually it was to cost £191 million, a fortune by 1901 standards, and many hundred times that amount in modern times.

The Boers’ guerrilla campaign also took a military toll on the British. Losses mounted and the failure of the blockhouse system to stop the attacks became a serious problem.

Exasperated, the British military decided that the only way to halt the Boers’ campaign was to cut off their supplies. To this end, the British built what eventually became forty-five concentration camps, designed to detain the rural Boer population, women and children alike. In addition, the farms were burned down in a scorched earth policy designed to break Boer resistance for once and for all.

The internment policy resulted in the unintended deaths of large numbers of Boer women and children. By the end of the war, some 27,927 deaths were recorded in the camps, 22,074 of whom were children under the age of sixteen. This death toll mean that just under 15 percent of the Boer population of both republics had died in the camps.

Threat of Extermination Forces Boer Surrender

Although the guerrilla war was reasonably successful (with one commando under the leadership of Boer General Jan Smuts raiding so far behind British lines that they came within sight of Cape Town), the pressures brought to bear by the concentration camps forced them to surrender or face extermination. The decision was taken to halt the guerrilla war and formally surrender, an act which was formalized by the 1902 Treaty of Vereeniging.

Some 7,091 British soldiers were killed in the war, compared to 3,990 Boer soldiers. The military losses were therefore eclipsed by the camp deaths, and it is estimated that the white population of South Africa would have been three times as large as it eventually became, were it not for the civilian causalities during the war.

The British authorities erected concentration camps in South Africa to cut off the rural support base of the Boer guerrilla armies during the Second Anglo–Boer War (1899–1902). Large numbers of Boer women and children died in these camps of hunger, malnutrition, and typhus. One survivor, Alie Badenhorst, wrote in her diary: “Worst of all, because of the poor food, and having only one kind of food without vegetables, there came a sort of scurvy amongst our people. They got a sore mouth, and a dreadful smell with it; in some cases the palate fell out and the teeth, and some of the children were full of holes or sores in the mouth. And then they died . . . the mothers could never get them anything . . . there were vegetables to be bought outside, but the head of the camp was strict and did not allow them to go out of the camp . . . For it was this day, the 1st December, that old Tant Hannie died . . . I never thought with my eyes to see such misery . . . tents emptied by death. I went one day to the hospital and there lay a child of nine years to wrestle alone with death. I asked where could I find the child’s mother. The answer was that the mother died a week before, and the father is in Ceylon (a prisoner of war) and that very morning her sister of 11 died. I pitied the poor little sufferer as I looked upon her . . . there was not even a tear in my own eyes, for weep I could no more. I stood beside her and watched until a stupefying grief overwhelmed my soul . . . O God, be merciful and wipe us not from the face of the earth” (Alida Badenhorst, translated E. Hobhouse, Tant Alie of Transvaal: Her Diary 1880–1902, George Allen and Unwin, London, 1923).

British Endorse Boer Policy toward Blacks

The Boer policy of denying citizenship and voting rights to blacks was endorsed and maintained by the British administrations in the former republics. The only exception to this rule had been in the Cape Colony, where a small number of Cape Coloreds qualified for the franchise under a strenuous property-owning qualification system.

Racial segregation was the norm across the country to such an extent that it was not even considered necessary to legislate on the matter. In this way the administration of the four colonies was carried out exclusively by whites, and, in the two former Boer republics, even by civil servants who merely returned to their prewar jobs.

The Union of South Africa 1910

In 1909, talks were started between the administrations of the four colonies about unification into one country. After protracted discussions, a constitution was agreed upon and the Union of South Africa was created in 1910. This state was a dominion under the British monarchy in a manner identical to the other dominions of Canada and Australia.

Cape Town was selected to be the legislative capital, Pretoria the administrative capital, and Bloemfontein the judiciary capital. The new country’s constitution specifically kept the already established policy of only allowing Europeans the vote, a clause which could only be changed by a two-thirds majority vote in the parliament.

Black “Homelands” Created Based on Traditional Territories

The Union of South Africa attempted to come to grips with the issue of land and the native population by passing the 1913 Land Act. This law divided the country into white and black areas, with the black tribes being apportioned land based on their areas of occupation before the advent of European colonization.

The British-ruled territories in Southern Africa which were not part of the Union, were also defined on a tribal basis. The Sotho tribe was given Lesotho, the Tswana tribe was given Botswana, and the Swazi tribe was given Swaziland. All three of these nations were eventually given independence and are still separate nations.

In a similar manner, the tribal homelands inside South Africa were formally identified and defined: Zululand was allocated to the Zulus, Transkei to the Xhosa, and so on. The previously unoccupied areas which had been colonized by the European settlers were designated as white territory.

Black resistance to the Union of South Africa’s racial policies emerged soon after its creation. In 1912, the African National Congress (ANC) was founded and for the next eighty years was the main opposition to white rule.

Attempts at Boer–Brit Reconciliation Fail

The largest party in the new Union’s parliament was called the South African Party (SAP), and was led by former Boer War General Louis Botha. The SAP had as one of its polices a program of reconciliation between “Boer and Brit,” as the divide was known. This attempt to create a racial unity led to the creation of a new generic term for all whites living in the Union, “South Africans,” and the terminology “Boer and Brit’ gradually faded away.

The Old Dutch language spoken by the Boers had been formalized into a more distinct dialect in the Cape during the last part of the nineteenth century, and had taken on the name Afrikaans. As it replaced Old Dutch, those who spoke it were called “Afrikaanders” and later just Afrikaners, no matter if they were originally Boers from the former republics or not.

General J.B.M. Hertzog, the Boer War hero who founded the National Party (NP) in 1914 as a voice for Afrikaner nationalism. The NP first came to power in 1924. In 1934, Hertzog agreed to merge the NP with the rival South African Party of fellow Boer War General Jan Smuts to form the United South African National Party. A hard-line faction of Afrikaner nationalists, led by D.F. Malan, refused to accept the merger and split off into a “Purified National Party”(PNP). When Smuts brought South Africa into the Second World War on Britain’s side, Hertzog resigned from government and retired. The PNP and its allies defeated Smuts’ United Party in 1948. After the election victory, the PNP merged with some smaller allies and became the National Party once again. This was the party which remained in power until 1994, when, after accepting the demographic realities of South Africa, it handed the country over to black majority rule.

National Party Founded in 1914

The attempt to create white unity was rejected by a significant number of English and Afrikaans speakers alike, who hived off into separate parties with different geographical bases. Natal played host to the pro-English party, while support for the pro-Afrikaans faction was concentrated in the Transvaal and Orange Free State.

In 1914, another of the Boer War generals, James Hertzog, broke with the SAP and founded a new group which he called the National Party, or NP. It was this party which was to dominate South Africa for most of the twentieth century and become famous for its association with Apartheid, or racial segregation.

At the time of its founding, however, the NP’s policy toward nonwhites was identical to that of the SAP and the pro-English faction, in that black political rights were not even considered an issue. The NP was founded to bring about equality between Afrikaans- and English-speakers, and then ultimately to reestablish Afrikaner rule.

World War I and the 1914 Boer Rebellion

The outbreak of the First World War split the whites politically even further. Many Afrikaners, still smarting after the Second Anglo–Boer War and the terrible memory of the British concentration camps, instinctively backed Germany against Britain.

The SAP government, even those former Boer leaders who dominated that party, were however loyalists, and declared war on Germany in support of Britain. The newly-formed Union Defence Force (UDF) was tasked with seizing the neighboring German colony of German South West Africa (later called South West Africa and today known as Namibia).

The decision to go to war on the side of the British was a step too far for many Boers, and a rebellion broke out, led by a number of former Boer War generals, including the famous Christiaan Beyers, Koos de la Rey, Jan Kemp, and Manie Martiz. Kemp and Maritz were senior figures in the UDF and the latter was in command of one of the large army units entrusted with attacking the Germans across the border.

Maritz and a large number of his soldiers deserted to the Germans. He then issued a proclamation of independence for the Boer republics and invaded the Northern Cape. De Wet raised a commando and seized the town of Heilbron in the Orange Free State, while Beyers gathered a commando outside Pretoria. Eventually over twelve thousand Boers rallied to the rebel cause, and the government was forced to postpone the invasion of German South West Africa to suppress the uprising.

The better equipped UDF defeated all the rebel forces and arrested the surviving ringleaders, who all received light prison sentences and were then released. De la Rey had been shot dead at a police roadblock in an unrelated incident at the start of the rebellion, and Beyers drowned in the Vaal River while fleeing government forces.

The suppression of the rebellion allowed the UDF to proceed with the invasion of German South West Africa, a task which was completed by July 1915. The UDF was also deployed in the seizure of the colony of German East Africa (modern Tanzania) and served with distinction on the Western Front in France.

The NP polled well in the 1915 election, although the SAP still held onto a slim majority in parliament after drawing more support from the English-speaking sector of the population which supported the decision to go to war on Britain’s side.

German South West Africa was mandated to South Africa by the League of Nations after the end of the war, with the intention that it be prepared for eventual independence.

General Jacobus Herculaas de la Rey (1847–1914), known as Koos de la Rey, was the leading Boer military figure of the Second Anglo-Boer War and the major leader of the guerrilla war against the British. Despite his successes in the field, the Boers were forced to surrender after the British interned their women and children in concentration camps. De la Rey took part in the peace negotiations which ended the war, and in 1907 was elected to the new self-governing Transvaal Colony government. He retained his military rank, and commanded the government forces which put down strikes in Johannesburg in 1914. In September of that year, he was killed in a shooting at a police roadblock while on his way to consult with leaders of the Boer Rebellion, with a view to possibly joining in. The 1914 Rebellion broke out shortly after his funeral. Above, a photograph of De la Rey in the field during the Second Anglo—Boer War.

Racist Communists and the Rand Rebellion of 1921

The Communist revolution in Russia which created the Soviet Union served as an inspiration to Communist supporters all over the world, and South Africa was no exception. The South African Communist Party (SACP) was launched by a number of prominent South African Jews in Cape Town (where Karl Marx’s sister had made her home and where a local newspaper had been the world’s first commercial publication to publish any of Marx’s articles) and soon became committed to revolutionary activity.

At this time, however, no one, not even the Communists, gave serious consideration to black political involvement. As a result, when the gold mining industry decided to replace white laborers with black and Chinese workers in 1921, the SACP was one of the first to stand up for the rights of the white workers.

Tensions between the miners and the captains of industry heightened and the involvement of the SACP added a political dimension which elevated the conflict to more than just an industrial dispute. A miners’ strike escalated into a major uprising, which involved an attempted coup d’etat by armed workers. The rebellion was launched by the SACP under the banner “Workers Unite for a White South Africa.” The slogan was for long afterward a great source of embarrassment for the SACP, which later became one of the strongest proponents for black rule.

The Rand Rebellion was suppressed by the army and the police in a major military operation which involved the bombing of rebel strongholds in Johannesburg by the fledgling South African Air Force—the only time in history that city was bombarded from the air.

In 1922, the South African Communist Party (SACP) seized upon white working-class discontent with the mining houses that had imported nonwhite labor to replace“expensive” white workers. The SACP fomented a violent revolution centered in Johannesburg, in the hope of emulating the Soviet Union’s Communist Revolution of October 1917. To this end, an uprising took place in March 1921, called the Rand Revolt, led initially by the SACP with the official slogan of “Workers Unite for a White S.A.” A banner with this slogan can be seen in this crowd in Johannesburg.

National Party Wins Power in 1924

Although the Rand Rebellion was crushed, its message reverberated throughout South African politics. The National Party (NP) and James Hertzog fought the next general election on an undertaking to protect white workers from encroachment by nonwhites through the imposition of a color bar.

The policy was endorsed by the electorate, and the NP won the election, displacing the SAP which was seen to have supported the mining bosses. Race had entered South African politics for the first time, and the NP was determined to be associated with the topic from then on.

The new NP government was as good as its word: it duly introduced the first color bar legislation soon after taking office. It also extended the franchise to white women in 1930, and removed property and education restrictions on the right to vote.

Hertzog’s government made Afrikaans into South Africa’s second official language in 1925, and introduced the famous orange, white, and blue national flag which would only be disposed of when white rule ended in 1994.

The NP remained in power until 1933, when the effects of the Great Depression forced it into a coalition government with the SAP which was then under the leadership of another Boer War general, Jan Smuts. The following year, the NP and the SAP amalgamated to form the United South African National Party, or United Party, as it became more commonly known.

The United Party coalition governed South Africa until the advent of the Second World War in 1939. Hertzog advocated neutrality, once again not wishing to enter a war on the side of Britain, while his deputy, Smuts, advocated declaring war on Germany. Parliament voted narrowly in favor of going to war and Hertzog resigned.

A small faction of NP hardliners under the leadership of D.F. Malan refused to join the 1933 coalition with the SAP, and remained in opposition as the Gesuiwerde Nasionale Party (“Purified National Party” or PNP). Hertzog and his supporters joined the PNP when they resigned from the coalition, and the party reformed itself into the Herenigde Nasionale Party (“Reunited National Party”).

Militant Afrikaner Opposition to South African Participation in Second World War

Militant Afrikaners, whose political opinions varied from the pro-Nazi to the anti-British, were organized into a movement known as the Ossewa Brandwag (“Ox Wagon Sentinel”). This group engaged in numerous acts of sabotage and violence in a successful program to keep large numbers of Union Defence Force’s soldiers deployed inside the country’s borders, rather than against the Germans. The OB was disbanded after the war.

Ossewa Brandwag leader Johannes van Rensburg arrives at a mass rally of supporters, circa 1940.

Despite the Ossewa Brandwag’s efforts, the UDF took part in the campaigns in Abyssinia, North Africa, and Italy. Jan Smuts won the 1943 election, and was made a field marshal by the British Army.

Smuts went on to be instrumental in the founding of the United Nations, a development which marked him as a politician with international standing. His racial policies ultimately were little different from that of his compatriots.

Reunited National Party Wins 1948 Election

The 1948 general election was won by the Reunited National Party even though Smut’s United Party polled the most votes (the result was skewed by the first-past-the-post electoral system which delivered more seats to the RNP). The party amalgamated with a minor election partner and changed its name once again into the “National Party.” It was this iteration of the NP which remained in power until 1994.

Dr. D.F. Malan (standing, right), leader of the Purified National Party, on the campaign trail in South West Africa in 1947. His party took power in the election in 1948, and was only dislodged in 1994 when the first all-race election was held.

The NP formalized the system of racial segregation in South Africa, but it was not the originator of that idea. As outlined earlier, racial segregation had been implemented from the time of the first European settlement. Even the policy of black homelands predated the 1948 NP. The tribal territorial areas were acknowledged as such in the nineteenth century and given formal legal recognition by the 1913 Land Act.

Nonetheless, it was the NP’s formalization of the policy and the use of the word apartheid, or in English, “separateness,” which exemplified South African segregation. The NP implemented a series of laws which formed the basis of their policy. The Prohibition of Mixed Marriages Act of 1949 outlawed interracial marriages; the Immorality Amendment Act of 1950 outlawed sex across the color line; the Population Registration Act of 1950 classified all inhabitants according to race, and created a Classification Board to make a final decision on a person’s race in disputed cases; the Group Areas Act of 1950 delineated separate racial residential areas; and the Reservation of Separate Amenities Act of 1953 enforced the segregation of all public facilities.

The South African Communist Party had in the interim renounced its racist past and worked against the white government. It organized trade unions, strikes, and general unrest, with the result that the NP passed the Suppression of Communism Act in 1950 which outlawed the SACP.

Black Resistance to Apartheid

Black resistance to the imposition of these laws grew as well. This resistance was initially peaceful, but after it became clear that the white government was not going to be persuaded by any other means, the African National Congress and other smaller resistance groups opted for a campaign of violence. This decision was given impetus after the ANC was banned following the shooting of a large number of black demonstrators outside a police station in Sharpeville, south of Johannesburg, in 1960.

The ANC launched its campaign of violent resistance the same year and maintained it, with varying degrees of success for another thirty years. The real power of black resistance lay, however, not in the limited program of violent resistance, but rather in their ability to bring the economy to a halt through strikes and industrial unrest. Once again, as in Haiti and the American south, the white population fell victim to its own reliance on black labor.

1961: The White Republic

The era of decolonization in Africa, which started in the 1950s and 1960s, set the white rulers of South Africa at odds with Britain. The NP took advantage of the increased political tension to achieve another long-term Afrikaner nationalist aim, and declared South Africa a republic, free of the British crown and Commonwealth, in 1961. The country’s name was changed from the Union of South Africa to the Republic of South Africa.

The republic was noted for many things apart from the policy of apartheid. The world’s first heart transplant was performed by an Afrikaner surgeon, Chris Barnard, in the segregated hospital of Groote Schuur in Cape Town in 1962, and the world’s first truly successful oil-from-coal conversion plant was created at Sasolburg in the Orange Free State. South Africa became self-sufficient in a large number of sophisticated manufacturing processes, including arms, and developed its own nuclear weapons.

Above right: A poster issued during the 1961 referendum when white voters were asked if they wished to make South Africa a republic or not. The poster made the issue at stake very plain: either stay in the British-led Commonwealth and be forced to accept black rule, or break away and become a white-ruled republic. A slim majority of voters chose the white republic option. The government and its supporters simply ignored the fact that the vast majority of the population was already nonwhite. Above left: Dr. H.F. Verwoerd, the Dutch-born National Party Prime Minister, who is widely, but incorrectly, credited with creating apartheid. In reality, the groundwork for the policy of segregation had been laid more than a century before the advent of the NP. Verwoerd was regarded as white South Africa’s greatest prime minister, and was twice a target for leftist assassins. The first assassination attempt, in which he was shot in the face, failed, but the second, carried out by a mixed-race orderly working in the South African parliament, was successful. Verwoerd was stabbed to death at his seat in the parliamentary building in September 1966.

“Grand Apartheid” and the Black Homelands

It was during the 1960s that the policy known as “Grand Apartheid” was formulated by the NP under the direction of its leader and Prime Minister Hendrik Verwoerd. This policy entailed taking the already recognized traditional black tribal areas and turning them into independent states, in exactly the same way that Britain had created tribal states for the Tswana, the Swazi, and the Sotho people.

The critical difference, however, which Verwoerd and the NP ignored, was that vast numbers of blacks in South Africa did not live in these tribal areas. The huge back city of Soweto, for example, which provided the labor force upon which Johannesburg and many of the Rand mines depended, was created by the Verwoerd government at the same time as the black homelands. Eventually there would be more blacks in Soweto and other black settlements around Johannesburg than all the whites in South Africa put together.

The attempts to create independent black homelands met, therefore with failure on the demographic front, and on the political front as well. No other country in the world recognized the handful of homelands which opted for independence as legitimate, and the leaders of those territories were uniformly rejected as puppets by the vast majority of blacks.

The Failure of Apartheid

Apartheid was doomed from the beginning as it refused to acknowledge the reality of demography and race. This ideology was based in archaic white supremacism, which advocated paternalistic rule over blacks rather than separatism.

Apartheid was designed to use millions of blacks as labor and to integrate them into the economy, but then to segregate them politically and socially. The white government refused to adjust the size of the black homelands to be in accord with the demographic reality, and stubbornly insisted that their land area—some 13 percent of the country’s surface—could accommodate 80 percent of the total population.

At the same time, Western medicine was made available to the black population on a massive scale. The largest hospital in the Southern hemisphere was built, financed, and subsidized by the white government in Soweto, and infant mortality rates among blacks plummeted while their reproduction rates remained constant.

In addition, white South Africa’s fate was sealed with their insistence upon the use of black labor. Nearly every white household employed at least one black servant, and often more. The Afrikaner farmers often had dozens, if not hundreds, of laborers on their farms, and the mines, which were the economic heart of the country, employed hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of blacks over the decades.

One of the laws introduced by the apartheid government illustrated perfectly the inherent contradiction in the application of its policy. The Pass Laws Act of 1952 stipulated that all blacks over the age of sixteen had to carry what was called a “passbook” with them at all times. This passbook contained individual endorsements as to where, and for how long, that black person could remain in an area. A black who obtained employment in a “white area” would have his or her passbook endorsed as such. The law stipulated where, when, and for how long a person could remain.

No one in the government appeared to appreciate that the Pass Laws Act made the swamping of the “white areas” inevitable, given the complete reliance of all industry, farming, and labor upon the black population.

The end result of all these factors was predictable: the white population of South Africa was overrun demographically by a racial time bomb of their own making. By 1990, there were less than five million whites in South Africa and more than forty million nonwhites. The maintenance of segregation under these circumstances was impossible and could not be maintained even by force of arms.

Central Johannesburg in the mid-1970s. A white policeman checks a black laborer’s“passbook”—a document which entitled the holder to be present in the white urban areas of South Africa, provided that he or she had a job. Nothing better illustrated the inherent flaw in apartheid than this bizarre situation where black workers were specifically granted permission to live and work in the so-called “white” areas of the country, while supposedly simultaneously trying to create a separate white society.

The Race War in South West Africa

German South West Africa had, it will be recalled, been handed to South Africa by the League of Nations after the First World War to prepare it for independence. However, successive South African governments had no desire to hand that territory over to its natives. By the 1960s, South West Africa had been de facto incorporated into South Africa, had representatives in the Cape Town parliament, and had the policy of apartheid enforced within its boundaries.

Native resistance had been founded and grew steadily in the form of the “South West African Peoples’Organization” (SWAPO). A campaign of violence was started which eventually required the deployment of the republic’s South African Defence Force (SADF). As was also the case with the South African black resistance, SWAPO received considerable support from the Soviet Union and other Communist bloc countries. In addition, the black resistance movement operated with the overwhelming support of the native population and was also able to exert considerable economic influence.

The war in South West Africa grew in intensity after the Portuguese withdrew control from their colony of Angola, which lay directly to the north. Freed of the anti-colonial combat in Angola, SWAPO and its allies were able to use that nation as a base from which to attack the South African forces in South West Africa.

In response, the SADF invaded Angola in 1975, and for many years thereafter maintained a military presence in the south of that country in what would ultimately be a futile attempt to halt SWAPO’s military campaign. Eventually some 1,200 SADF soldiers were to die in the war in South West Africa and Angola before South Africa finally admitted defeat and handed over power to SWAPO in 1990.

South Africa gained control of the German colony of South West Africa (today called Namibia) during the First World War and retained authority there until 1990. This led to an insurgency by the black South West African People’s Organization (SWAPO). The collapse of the Portuguese colonial empire in 1975 allowed SWAPO to launched guerrilla attacks on South African forces from neighboring Angola, and a border war erupted between the South African Defence Force and the Soviet-and Cuban-backed Angolan army, which lasted from 1966 to 1989. The South African Army penetrated deep into Angola in pursuit of SWAPO and the Angolan forces, but neither side managed to clinch a definitive victory. In 1990, the South Africans withdrew and turned South West Africa over to SWAPO rule.

Internal Security Crisis Worsens

Despite the South African military establishment being the most powerful in Africa, the low level guerrilla war and campaign of economic sabotage could not be countered with a conventional army. As the white government refused to acknowledge the racial demographic reality, it resorted to ever more extreme security measures in an attempt to keep control of the country.

In 1976, a black student uprising in Soweto marked an upsurge in violent civil unrest. Although the unrest was initially suppressed with the loss of over five hundred black lives, the “Soweto Riots,” as they became known, marked a watershed in the racial divide in South Africa. From then on, international opinion was mobilized against white South Africa and the black resistance was able to maintain mass civil unrest in almost every urban center for the next fifteen years.

In response to this development, the South African Police were given the right to hold people indefinitely without trial and implemented numerous other draconian measures, which included covert assassination and anti-terrorist teams. The state was forced to declare an almost continuous state of emergency after 1976 but this did nothing to halt the ever-increasing waves of civil unrest, armed conflict, and economic sabotage which reached an all-time high in the 1980s.

A scene from the famous 1976 Soweto Riots which sums up the racial demographic situation well. From that year onward, the sixty thousand-strong South African Police fought an untenable and unsustainable war against continuous riots and an ever-intensifying African National Congress campaign of violence and sabotage. Ultimately, the South African security forces would simply be overwhelmed by numbers.

The NP attempted partial reforms of apartheid as a means of alleviating some of the building pressure. A new constitution introduced in 1983 created a mixed-race parliament to which Indians and Cape Coloreds could be elected—albeit on separate voters’ rolls—and by the mid-1980s many apartheid laws, such as the Pass Laws Act, the Mixed Marriages Act, the Immorality Act, the Group Areas Act, and the Reservation of Separate Amenities Act, had been repealed.

These reforms did nothing to halt the ANC’s campaign for complete political reform, and the increased freedoms accorded by the repeal of many of the apartheid laws only resulted in greater unrest as the underground resistance found it easier to move around the country and organize. The campaign of violence actually increased in intensity in direct proportion to the repeal of the restrictive laws.

Power Handed over to ANC 1994

Finally, the white government was forced to confront the reality of the demographic disaster which had been created over the previous century. Faced with the choice of fighting a no-hope race war and ultimately being defeated by sheer numbers, or giving over without a fight, the NP chose the latter.

In 1990, the ANC and its allied organizations (the SACP included) were unbanned, its imprisoned leader Nelson Mandela freed, and negotiations started to bring about the end of white minority rule. Within four years, the first election based on universal suffrage was held and the ANC took power with nearly two thirds of the vote. White rule was finally at an end.

The decision to surrender power was contested by white hard-liners, who formed a number of opposition groups both inside and outside parliament during the 1980s. None were, however, able to defeat the NP in either the elections or the two referendums that were held during the reform years.

The most prominent extra-parliamentary group was called the Afrikaner Weerstandsbeweging (Afrikaner Resistance Movement, or AWB), which launched an extended campaign of violence and terrorism in 1994 just prior to the first universal suffrage elections. The white militants were all quickly arrested and the campaign failed to prevent the inevitable.

The Failure of White Supremacy

The white population of South Africa went into dramatic decline in the years following 1994, and official figures show that one-third had emigrated within the first ten years. Factors which caused this massive white flight included a serious black crime problem, affirmative action which discriminated against whites, and economic decline as South Africa started its inevitable shift to Third World status.

The rise and fall of white South Africa serves as the premier modern example of the power of racial demographics as a final determinant in the rise and fall of any civilization or culture. It is also conclusive evidence that white supremacy, or white attempts to rule over masses of nonwhite people, is a recipe for disaster. The reality remains that the only guarantee for any individual civilization’s survival is separatism.

This is a chapter from March of the Titans, The Complete History of the White Race, available here.

as a white born citizen of South Africa who partook in the final resistance to black majority rule in the role as a national serviceman in the 80’s i am able to state that the authors research and ultimate explanation to the failure of white rule in our country is based on fact and thus correctly interpreted. Credit must be given to this enlightment and to the extensive research that was needed to explain why and how a first world country fell to its present day status.Thank-you for the revelation and logical explanation,i found it not only interesting and knowledgable but also the truth as to why my birth country finds itself where it is to-day.