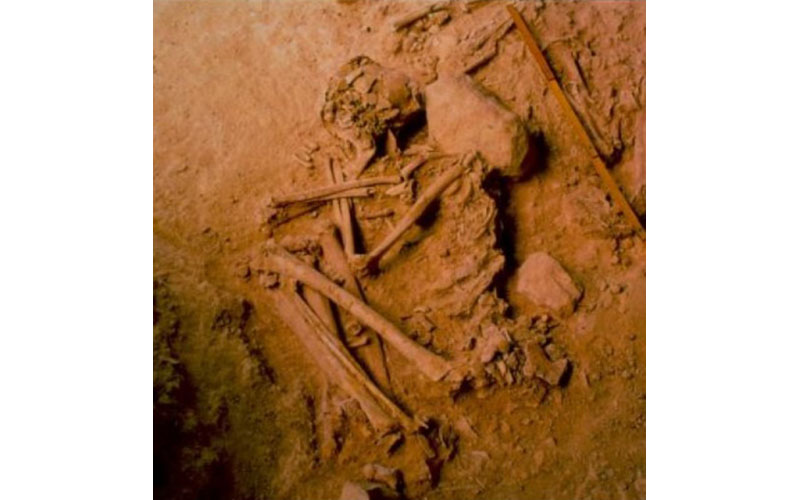

Archaeological remains of individual MC337 excavated from the site of Hipogeu de Monte Canelas I, Portugal, and analysed by the archaeologist Rui Parreira and the anthropologist Ana Maria Silva.

The genomes of individuals who lived on the Iberian Peninsula in the Bronze Age had minor genetic input from Steppe invaders, suggesting that these migrations played a smaller role in the genetic makeup and culture of Iberian people, compared to other parts of Europe.

Daniel Bradley and Rui Martiniano of Trinity College Dublin, in Ireland, and Ana Maria Silva of University of Coimbra, Portugal, report these findings July 27, 2017 in PLOS Genetics.

Between the Middle Neolithic (4200-3500 BC) and the Middle Bronze Age (1740-1430 BC), Central and Northern Europe received a massive influx of people from the Steppe regions of Eastern Europe and Asia—the Indo-European invasions.

Archaeological digs in Iberia have uncovered changes in culture and funeral rituals during this time, but no one had looked at the genetic impact of these migrations in this part of Europe.

Researchers sequenced the genomes of 14 individuals who lived in Portugal during the Neolithic and Bronze Ages and compared them to other ancient and modern genomes.

In contrast with other parts of Europe, they detected only subtle genetic changes between the Portuguese Neolithic and Bronze Age samples resulting from small-scale migration.

However, these changes are more pronounced on the paternal lineage.

“It was surprising to observe such a striking Y chromosome discontinuity between the Neolithic and the Bronze Age, such as would be consistent with a predominantly male-mediated genetic influx” says first author Rui Martiniano.

Researchers also estimated height from the samples, based on relevant DNA sequences, and found that genetic input from Neolithic migrants decreased the height of Europeans, which subsequently increased steadily through later generations.

The study finds that migration into the Iberian Peninsula occurred on a much smaller scale compared to the Steppe invasions in Northern, Central and Northwestern Europe, which likely has implications for the spread of language, culture and technology.

These findings may provide an explanation for why Iberia harbors a pre-Indo-European language, called Euskera, spoken in the Basque region along the border of Spain and France.

It has been suggested that Indo-European spread with migrations through Europe from the Steppe heartland; a model that fits these results.

Daniel Bradley says “Unlike further north, a mix of earlier tongues and Indo-European languages persist until the dawn of Iberian history, a pattern that resonates with the real but limited influx of migrants around the Bronze Age.”

- Paper: Rui Martiniano, Lara M. Cassidy, Ros Ó’Maoldúin, Russell McLaughlin, Nuno M. Silva, Licinio Manco, Daniel Fidalgo, Tania Pereira, Maria J. Coelho, Miguel Serra, Joachim Burger, Rui Parreira, Elena Moran, Antonio C. Valera, Eduardo Porfirio, Rui Boaventura, Ana M. Silva, Daniel G. Bradley. The population genomics of archaeological transition in west Iberia: Investigation of ancient substructure using imputation and haplotype-based methods. PLOS Genetics, 2017; 13 (7): e1006852 DOI: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006852

Its possible rather than mass movements dna entered slowly from gene exchange same happened with language farming and culture. It would explain variations maybe Basques were more isolated linguistically and culturally and so resisted those changes. Although gene flow did happen but less.