Afrocentrist claims that Africans originated Europe’s oldest civilization in Crete have been nixed by a new DNA study which has shown that the original population of that island were European.

The theory that Africans, not Europeans, created the Minoan civilization which flourished from around 2,700 BC to 1,420 BC, has been popularized by the Jewish Professor Emeritus of Government and Near Eastern Studies at Cornell University, Martin Bernal, in his book Black Athena: The Afroasiatic Roots of Classical Civilization.

In that book, now wildly quoted by Afrocentrists, Bernal claimed that Greece’s African and Asiatic neighbors, especially Ancient Egyptians and Phoenicians, had an influence on ancient Greece. Bernal proposes that a change in this Western perception took place from the 18th century onward and that this change fostered a subsequent denial by Western academia of any significant African and (western) Asiatic influences on ancient Greek culture.

Now however, a new report published in the journal Nature Communications, has definitively rebuffed this Afrocentrist hijacking of ancient European civilization.

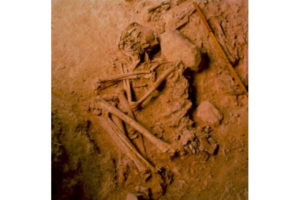

The report, “A European population in Minoan Bronze Age Crete,” analyzed and compared DNA extracted from 4,000-year-old Minoan skeletons with genetic material from people living throughout Europe and Africa in the past and today.

“We now know that the founders of the first advanced European civilization were European,” said study co-author George Stamatoyannopoulos, a human geneticist at the University of Washington. “They were very similar to Neolithic Europeans and very similar to present day-Cretans,” residents of the Mediterranean island of Crete.

Theories about why the Minoan civilization vanished have abounded, but the most likely cause is a combination of natural disasters (the volcanic eruption of Santorini) and the Indo-European Mycenaean invasion.

The research team analyzed DNA from ancient Minoan skeletons that were sealed in a cave in Crete’s Lassithi Plateau between 3,700 and 4,400 years ago. They then compared the skeletal mitochondrial DNA with that found in a sample of 135 modern and ancient populations from around Europe and Africa.

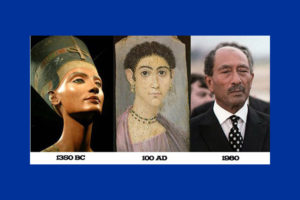

They found that the Minoan skeletons were genetically very similar to modern-day Europeans—and especially close to modern-day Cretans, particularly those from the Lassithi Plateau. They were also genetically similar to Neolithic Europeans, but distinct from Egyptian or Libyan populations.

The findings also confirmed that the ancient Minoans were descended from a branch of agriculturalists from the presumed Indo-European homeland around the Black Sea, who fanned out into Europe about 9,000 years ago.

The Minoans may have spoken a proto-Indo-European language derived from the one possibly spoken by those Anatolian farmers, the researchers speculate.

“The first Neolithic humans reached Crete about 9,000 years before present (YBP), coinciding with the development and adoption of the agricultural practices in the Near East and the extensive Neolithic population diffusion (8,000–9,500 YBP) that brought farming to Europe,” the report states.

“The most likely origins of these Neolithic settlers were the nearest coasts, either the Peloponnese or south-western Anatolia.

“Our calculations of genetic distances, haplotype sharing and principal component analysis (PCA) exclude a North African origin of the Minoans. Instead, we find that the highest genetic affinity of the Minoans is with Neolithic and modern European populations.

“We conclude that the most likely origin of the Minoans is the Neolithic population that migrated to Europe about 9,000 YBP. We propose that the Minoan civilization most likely was developed by the autochthonous population of the Bronze Age Crete.”